Alexandra Bilak

DIRECTOR, INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT MONITORING CENTRE (IDMC)

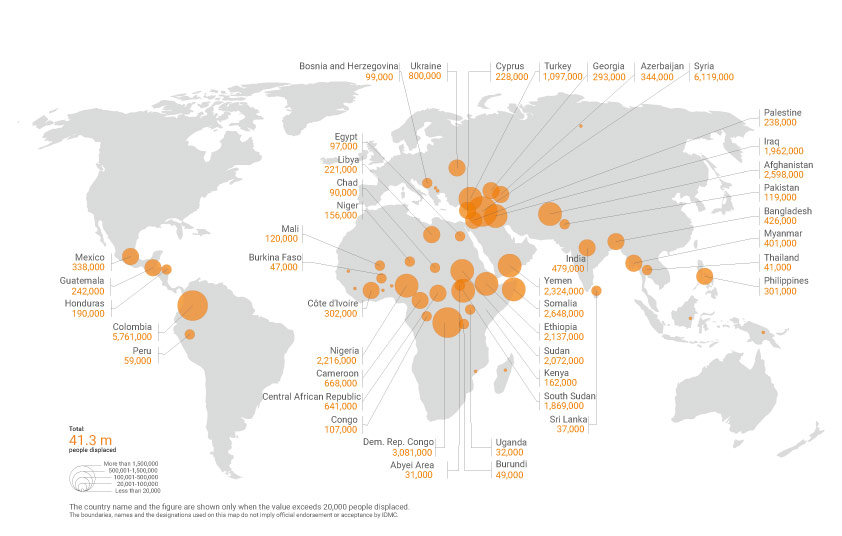

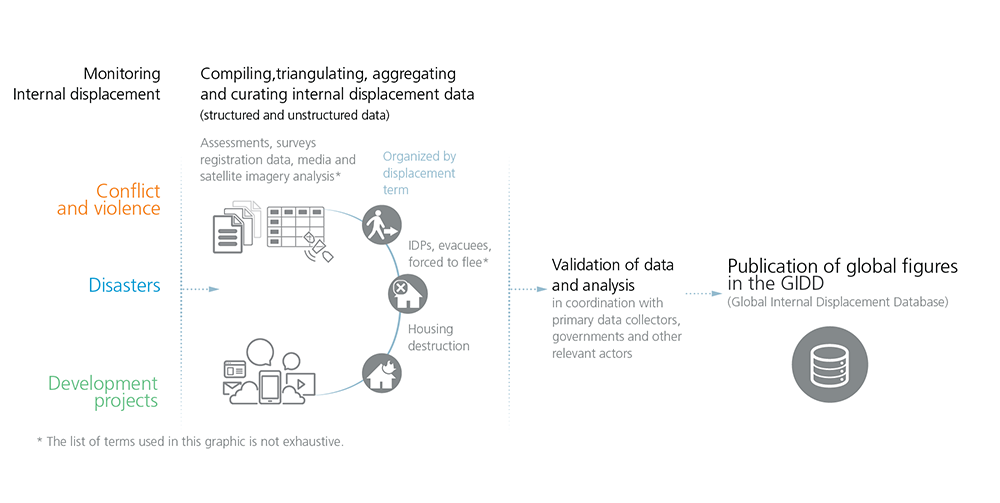

Alexandra Bilak was appointed director of IDMC in 2016. She has extensive experience in research and policy development on displacement in the context of conflict and violence, disasters, climate change and development investments. As Director, Alexandra is responsible for the strategy, positioning and resource mobilisation of the organisation, and for growing its reach and influence. Her role includes; establishing high-level strategic partnerships with governments affected by internal displacement, UN agencies, regional organisations and other relevant stakeholders. She leads the IDMC team to provide high-quality data, analysis and expertise on internal displacement with a view to finding policy and programmatic approaches that offer real solutions to internally displaced people. Under her direction, IDMC also addresses the gap between prevention and risk reduction, humanitarian response, state-building and sustainable development.

Prior to her appointment as Director, Alexandra served as IDMC’s Head of Policy and Research from 2014-2016. During this time, she developed a new research agenda in line with the global 2030 policy agenda, and produced new analyses into the drivers, patterns and impacts of internal displacement in different country contexts. Since 2014, she has directed the publication of IDMC’s annual flagship reports; the Global Overview, Global Estimates and Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID).

Before joining IDMC, Alexandra served as Country Director and Programme Manager for several international NGOs and research institutes in sub-Saharan Africa; including Oxfam, the Life & Peace Institute, the International Rescue Committee and the Danish Refugee Council. She has accumulated fifteen years' experience living and working in conflict and post-conflict contexts, and has published extensively on the themes of forced displacement, conflict and civil society development. Alexandra lived and worked in Rwanda in 2001, the Democratic Republic of Congo from 2004 -2008, in Kenya from 2009 - 2014, and has worked extensively across Central, East and West Africa.

Alexandra holds a Master's degree in International Politics from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and a DEA in African Studies and Political Science from the University of Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. She is fluent in English and French.

.jpg)

-bw.jpg)