Coronavirus crisis: internal displacement

Impacts

Coronavirus risk and new displacements

"It is still too early to fully grasp how Covid-19 will affect the tens of millions of people displaced inside their own countries – many of them fragile ones, with strained health systems and infrastructure. We can only imagine what it will mean for the women, men and children living in displacement camps, overcrowded slums or small apartments for whom access to clean water, healthcare and government support is limited, and who will suffer disproportionately from its impacts.

As the world gradually uncovers the devastating long-term consequences of this virus, the world’s internally displaced risk becoming the pandemic’s most tragic victims."

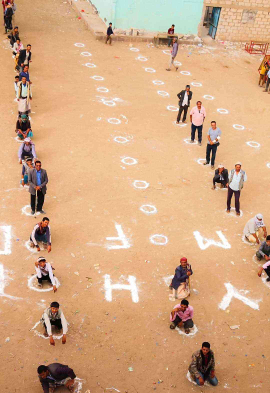

Alexandra Bilak, Director, IDMC (Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC)

Covid-19: Multiplying the risk of new displacements?