Expert analysis

21 June 2024

Canada’s Indigenous peoples increasingly at risk of disaster displacement

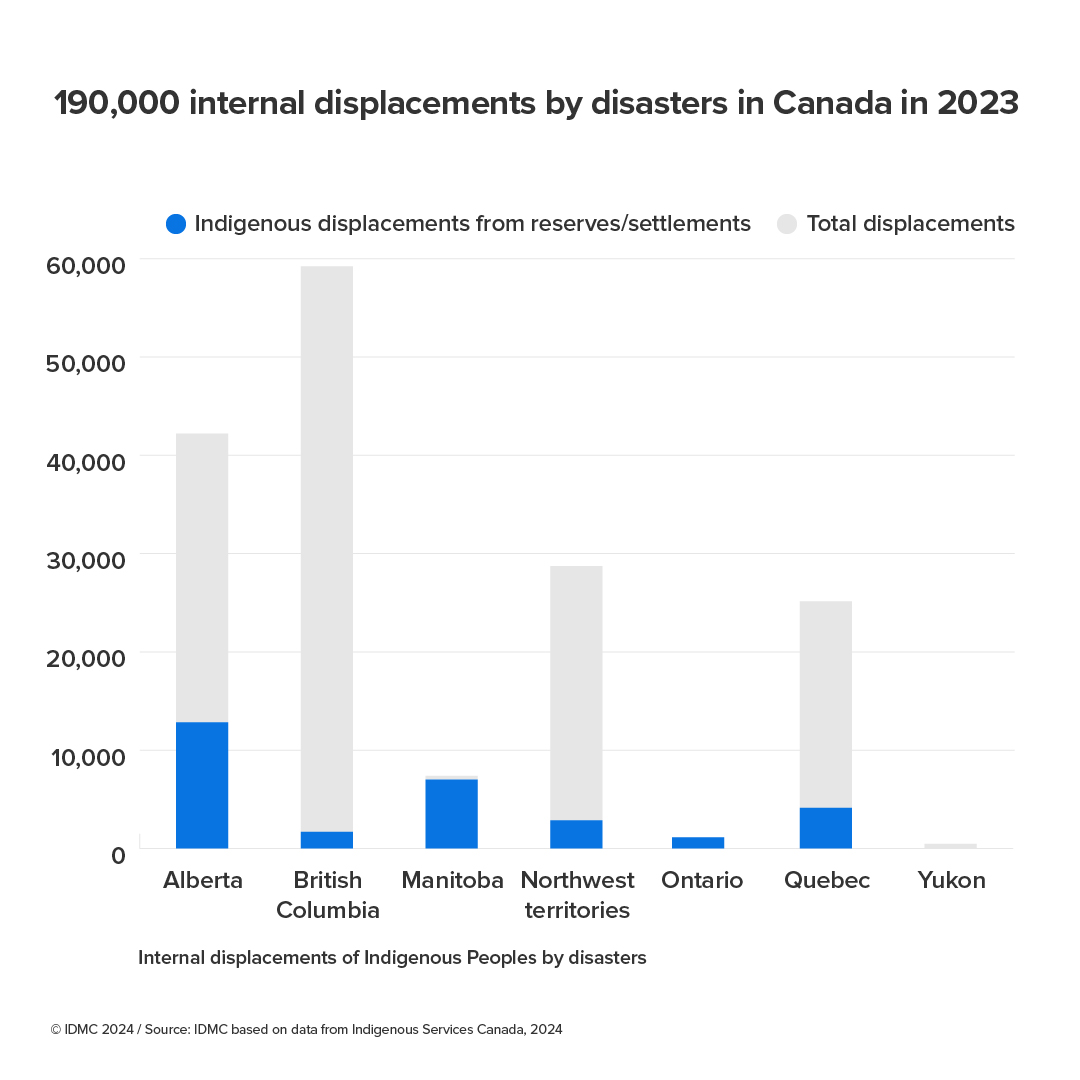

Although Indigenous peoples only represent 5 per cent (1.8 million people) of Canada’s population, over 16 per cent of the people internally displaced in Canada in 2023 were Indigenous peoples living on reserves.

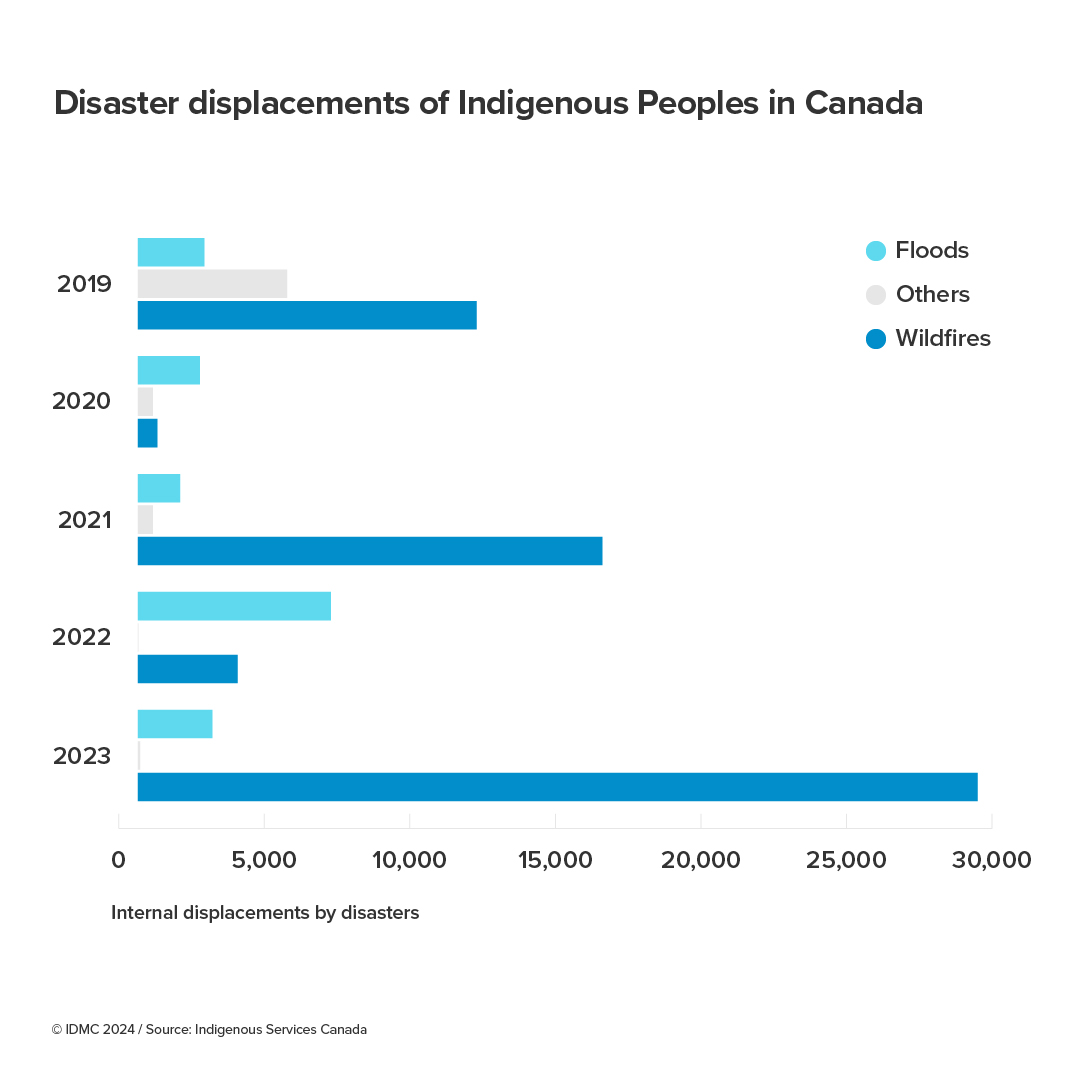

In 2023, IDMC documented a record of over 190,000 internal displacements due to disasters, primarily wildfires, in Canada. The country’s Indigenous peoples, which includes Métis, Inuit, and First Nations, were particularly affected by these events, accounting for around 30,000 displacements. Without special attention, displacement from more frequent and intense disasters threatens to weaken the wellbeing and resilience of Indigenous communities.

Unique and increased risks of displacement

Multiple factors contribute to this increased displacement risk, including the location of Indigenous communities, the lack of resources for disaster prevention and response, especially wildfires, and the overall increase in disasters affecting the country, a trend expected to continue due to climate change.

In the past, colonial practices and historical displacements drove many communities into isolation, away from their traditional lands to flood- and wildfire- prone areas. Today, reserves and communities are often in remote areas with low firefighting priority due to sparse population and limited infrastructure. Limited capacity and resources have shaped a policy of letting wildfires burn out as long as they do not affect key infrastructure or towns – particularly in the northern latitudes where many Indigenous peoples reside.

Indigenous communities are also at risk of repeated displacements.

The remoteness of many communities limits their ability to evacuate during disasters due to limited roads – often inaccessible during wildfires – and transportation. When the Northern Quebec Cree nation of Nemaska were called to evacuate five times in July 2023, they were forced to do so by boat due to lack of road accessibility. In August 2023, the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Community in Old Crow, Yukon, evacuated due to wildfires by plane as the community is not accessible by road.

Indigenous communities are also at risk of repeated displacements. Since 2012, the Kashechewan First Nation community in Northern Ontario now calls spring “evacuation season” after it experienced a dozen years of displacement when the Albany River floods. In 2006, the Kashechewan Chief drafted permanent relocation plans, which were approved by the federal government in 2019. Nevertheless, the plans have yet to be put into action.

Unique and increased risks during displacement

Due to their unique link and reliance on the environment, Indigenous communities also face increased challenges and vulnerabilities during displacement, particularly in relation to language, culture, and livelihoods. Continuous right to self-determination and respect for, and access to, traditions is key to the preservation of Indigenous culture.

Continuous right to self-determination and respect for, and access to, traditions is key to the preservation of Indigenous culture.

Many Indigenous communities strongly rely on fishing, hunting, and harvesting for their livelihood. Wildfires can make affected areas less habitable for the wildlife on which Indigenous communities rely for food. Furthermore, much of the identity, cultural practices and generational teachings of First Nations, Métis, and Innuits are directly related to their local environment.

When a major flood displaced the Siksika First Nation in 2013, many ended up displaced for at least six years. Upon return, not only was an estimated quarter of the land lost or rendered uninhabitable by the flood, but contaminated water and soil also reduced access to traditional medicine. As a result, the communities’ health and cultural identity suffered. The community relocated from their traditional clan lands, re-building homes along a dangerous highway.

For two years, sites consisting of modular mobile office trailers housed some Siksikas. Curfews and security check-ins for each movement in and out of the sites were imposed. Trailers lacked reliable heating and refrigerators. Cooking in the trailers was forbidden and they were unsuitable for people with mobility challenges or special needs. The Siksika’s long term displacement and subpar living conditions had a negative impact on their mental health, with some members stating they felt imprisoned or reminded of residential schools.

When fires forced residents of Yellowknife to evacuate in August 2023, some Indigenous peoples moved to urban areas. For many, this was the first time away from rural areas, adding to their challenges of being displaced. According to the Tłı̨chǫ Grand Chief (local First Nations), some elders, who speak neither English nor French, encountered difficulties during the evacuations as they were not provided with interpreters or language services. According to the Indigenous community, cooperation and collaboration between the Northwest Territory Government and the Tłı̨chǫ Government was lacking.

Need for Indigenous based disaster planning and response

When links to their environment are cut during and after displacement, the vulnerability of Indigenous communities increases. To minimize the impact of disasters and internal displacement on Indigenous peoples, there is a need for greater cooperation and collaboration between the Canadian authorities and the communities. Many Indigenous communities have criticized the lack of involvement in disaster preparedness and response, including life-saving preventive displacements. For instance, the Tłı̨ch�ǫ community’s government claimed that it was not asked where its community members should be evacuated to, nor how they could be supported during the evacuation of Yellowknife due to wildfires in 2023.

First Nation communities feel that government authorities have also failed to capitalise on Indigenous capacities and knowledge on disaster responses. The Tłı̨chǫ community argues it could have supported the Northwest Territory government in informing and identifying those in need. Similarly, the Dene First Nation regretted not being involved, and insisted that future decisions on evacuations should be grounded in the teachings of Elders and the Land. Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation also called for a renewed emergency and evacuation policy.

To minimize the impact of disasters and internal displacement on Indigenous peoples, there is a need for greater cooperation and collaboration between the Canadian authorities and the communities.

Local authorities in Canada have recently made efforts to better integrate Indigenous knowledge in fire response to improve collaboration and to include Indigenous peoples in the preventative stage of disaster management. Provincial governments and local authorities are now increasingly utilising cultural burnings, a practice that enhances biodiversity and reduces wildfire risk by reducing vegetation, but which had been banned for decades by provincial governments.

Another positive example is the National On-reserve All Hazards Emergency Management Plan established by Indigenous Services Canada in partnership with First Nation communities in May 2024. The Plan seeks to provide funding to First Nation communities to build resilience, prepare for natural hazards, and respond to the latter through prevention and mitigation of disaster risks; increase preparedness; responses which minimize the impact of emergencies, including but not limited to emergency public communication, search and rescue, and evacuations; and recovery actions to repair and restore conditions, such as the return of evacuees, trauma counselling, reconstruction, and financial assistance.

Throughout the application of the Plan, the Canadian federal and provincial governments should continue to cooperate with Indigenous peoples to combat wildfires and include the communities in discussions on environmental disaster risk mitigation. This will not only ensure Indigenous communities’ agency over how disasters are managed on their lands, but also contribute to minimising disaster displacement risks and vulnerabilities through more efficient and effective responses.