Expert analysis

24 November 2023

Evidence for action: Socioeconomic survey data is now available

To address the impacts of internal displacement, it is essential to understand how it affects the lives and resources of internally displaced people, the communities that host them and the governments responsible for them. Sadly, this information is rarely available to support decision makers in designing effective remedies.

To help fill this gap, IDMC developed a survey to reveal the social and economic impacts, costs and losses linked with internal displacement and to help estimate the return on investment in mitigating these impacts. To date, this survey is the only tool designed specifically to quantify the effects of displacement on livelihoods, health, education, security and housing conditions for both displaced and non-displaced communities in a standardized way across countries and contexts.

Contact us to learn about using the survey in your work

The financial costs and losses associated with internal displacement can be overwhelming for internally displaced people (IDPs) and their hosts and can overstretch governments’ capacities to respond. These costs and losses also vary from one situation to the next. The data available from IDMC’s survey is valuable for informing responses which are tailored to specific needs and prioritise activities with the greatest impact.

The financial costs and losses associated with internal displacement can be overwhelming for internally displaced people (IDPs) and their hosts and can overstretch governments’ capacities to respond.

As of 2023, IDMC had used this survey to collect primary data in selected locations in 14 countries, covering displacement due to conflict, violence, insecurity, floods, droughts, sea level rise, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. The data collected in Colombia, Ethiopia, Eswatini, Indonesia, Nepal, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Somalia and Vanuatu is available in earlier IDMC reports. It has already played a pivotal role in shaping humanitarian response strategies in Somalia and Nigeria. Similarly, in Colombia, the formulation of the humanitarian needs overview, response plan, and budget heavily depended on this data.

For the first time, the dataset and survey tool from the recent studies in Cameroon, Kenya, Mali, and Niger are now downloadable and ready for use. This blog explores specific analyses made possible by this valuable data.

Socioeconomic case studies 2023 code book

Livelihoods, housing, health and education data

The survey collects quantitative data, qualitative data and financial information to measure the impacts of internal displacement for use in humanitarian and development planning, budgeting and advocacy. Its methodology enables the analysis and measurement of both economic and non-economic losses and damages associated with internal displacement for both the surveyed IDPs and host communities (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The five impact dimensions measured by IDMC’s survey.

In terms of livelihoods, it explores income, work disruptions, financial support, employment opportunities and the ability to meet basic needs. For housing, it investigates ownership, costs, hosting expenses, and satisfaction. In health, it covers physical and mental well-being, food access, healthcare, and costs. In terms of security, it assesses perceptions, changes, and concerns, while in education, it examines access, barriers, costs, interruptions, quality, and support.

The survey maintains a consistent structure and wording across different countries to make it easier to identify broader trends, such as the consistent deterioration of IDPs’ income after displacement and the frequent interruption in schooling for internally displaced children. To reveal the varying vulnerabilities facing different IDPs, the survey allows for disaggregation by sex, age, disability status, income and education levels, area of origin, duration of displacement, ethnolinguistic identity and other factors. Capturing detailed data can expose overlapping vulnerabilities, such as language barriers that pose significant employment hurdles for IDPs or the difficulty in finding food, especially in households with disabled members.

Capturing detailed data can expose overlapping vulnerabilities, such as language barriers that pose significant employment hurdles for IDPs.

In early 2023, IDMC employed this methodology in specific locations in Kenya, Mali, Cameroon, and Niger. Each location involved surveys of approximately 300 internally displaced households and 300 non-displaced households in contexts of drought, insecurity, violence, and floods. The following key findings illustrate the potential analyses that can be derived from this data.

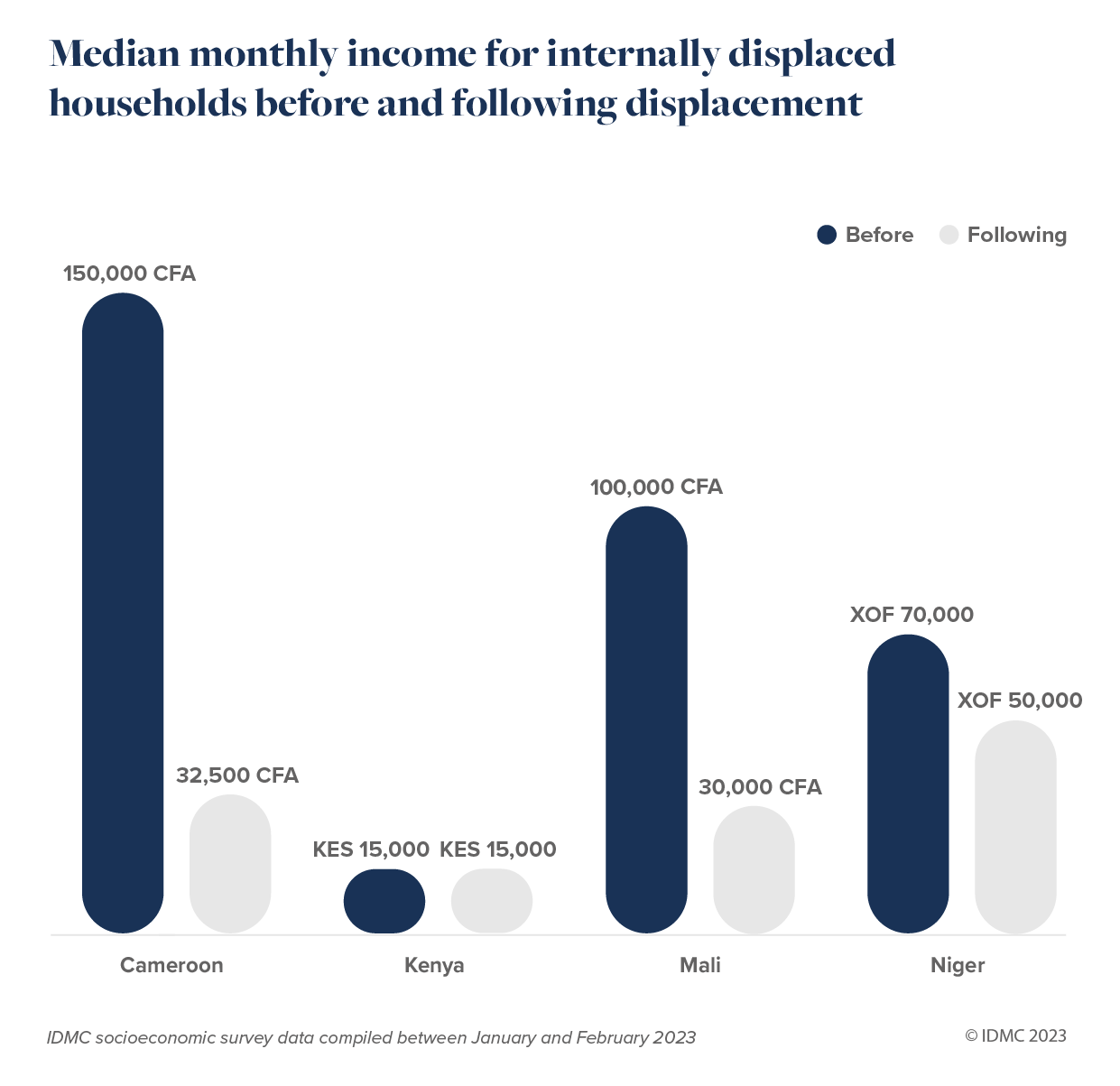

Livelihood and financial impacts

Displacement resulted in a substantial loss of household income for IDPs in all countries except Kenya, where no overall change occurred (see figure 2). The Kenya case study highlighted persistent economic challenges for both displaced and non-displaced respondents that were exacerbated by a lack of external financial assistance. Notably, it showed earning disparities based on disability. Before displacement, households with a disabled member earned less (8,000 KES) compared to those without (15,000 KES). Post-displacement, households with a disabled member saw a further income decrease (7,500 KES).

In Cameroon, 98% of displaced households surveyed had at least one member earning money from work before displacement, but that percentage dropped to 59% after displacement. In Mali, one-third of displaced households experienced income loss. Among these, those headed by male respondents post-displacement earned a median income one-third higher than their female-led counterparts, highlighting and exacerbating gender disparities in this context.

The survey also goes deeper with questions to assess IDP’s overall ability to meet their needs, differences between male and female-headed households and obstacles to employment.

Figure 2: Median monthly income for internally displaced households before and following displacement for all four countries.

Health impacts

Access to healthcare posed a significant challenge for IDPs in all studies, primarily due to cost. In Kenya, IDP respondents reported a median healthcare cost of 2,000 Kenyan Shillings before displacement, which rose to 2,500 Shillings after displacement. Non-displaced households also faced difficulties in accessing healthcare in the location surveyed in Kenya, where limited healthcare infrastructure led to overcrowding and inaccessibility.

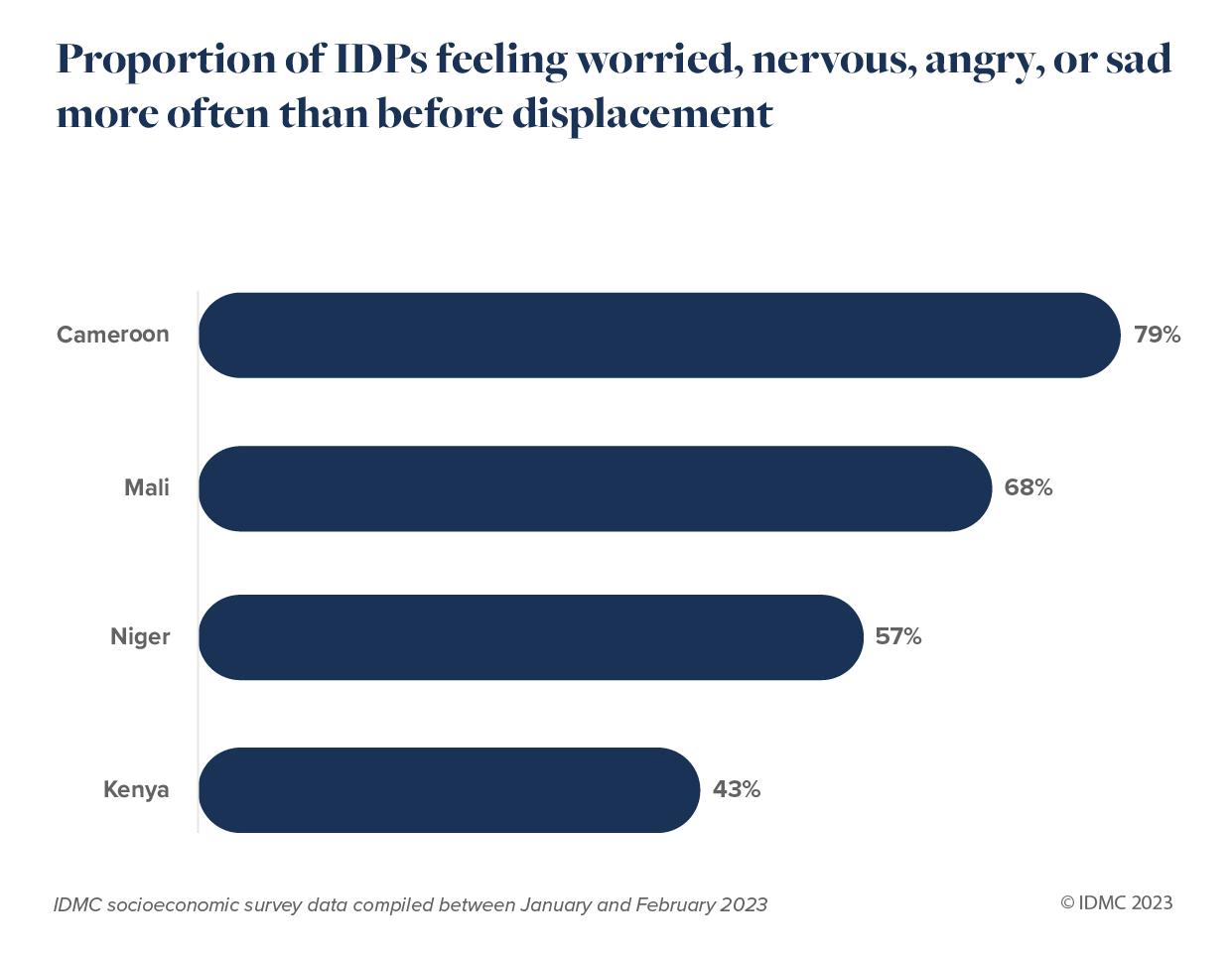

In terms of impacts on mental health, a significant proportion of IDPs across all four case studies reported increased feelings of worry, nervousness, anger, or sadness after their displacement (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportion of IDPs feeling worried, nervous, angry, or sad more often than before displacement.

Education impacts

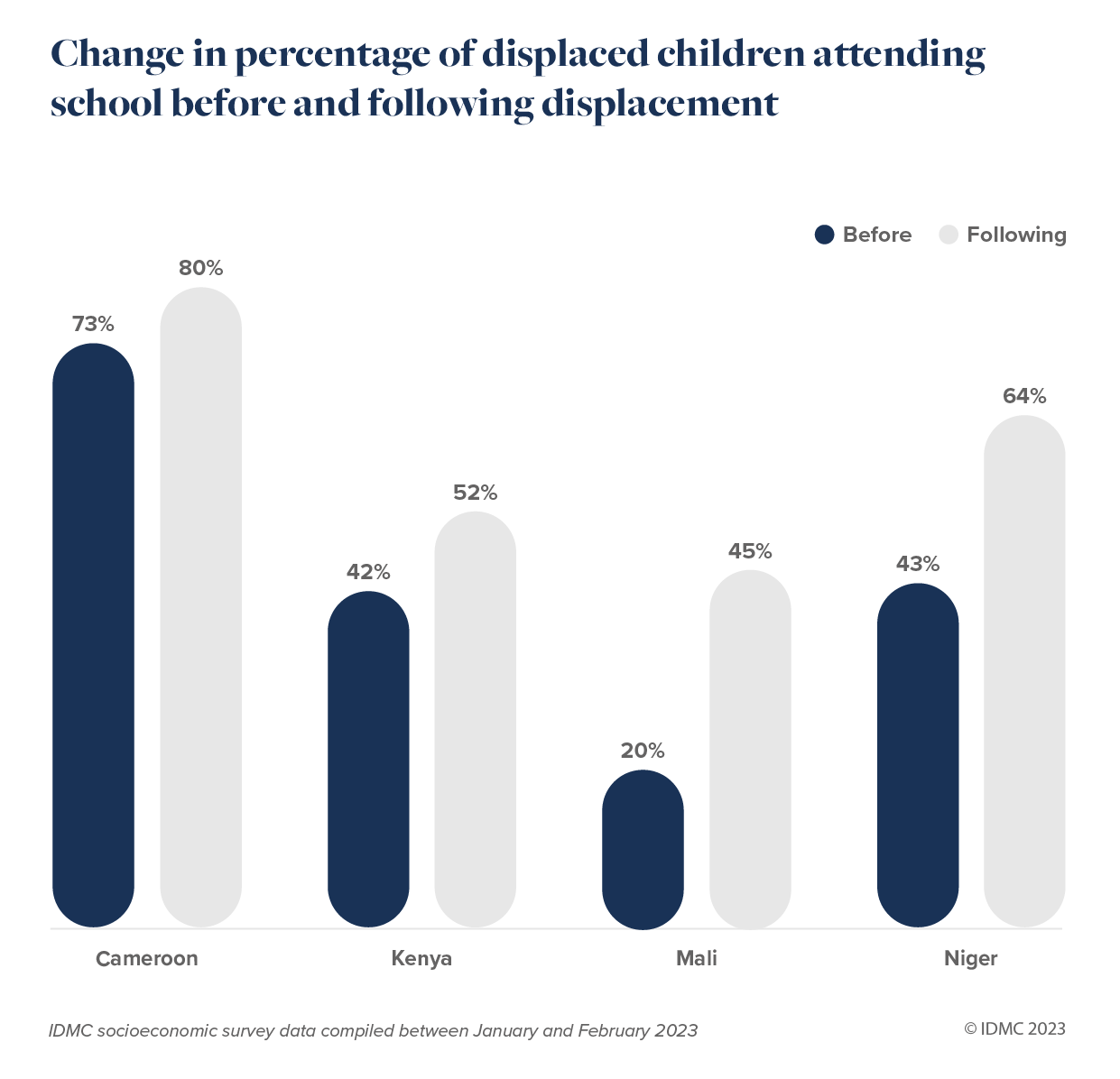

Internal displacement consistently disrupts the education of internally displaced children. In Mali, 64% of displaced children have faced interruptions exceeding a year, with 45% in Kenya and 80% in Cameroon experiencing similar disruptions. These interruptions significantly affect the overall quality of their learning and hinder their academic progress.

Notably, in the case studies conducted this year, a larger percentage of displaced children are now attending school compared to before displacement (refer to figure 4). This shift can be attributed to the fact that in these cases, IDPs have moved to urban or camp areas where education services are more readily accessible for their children than in their home areas. However, further research is warranted to evaluate the long-term effects of these schooling disruptions on their overall development and future opportunities.

Figure 4: Change in percentage of displaced children attending school before and following displacement.

Housing impacts

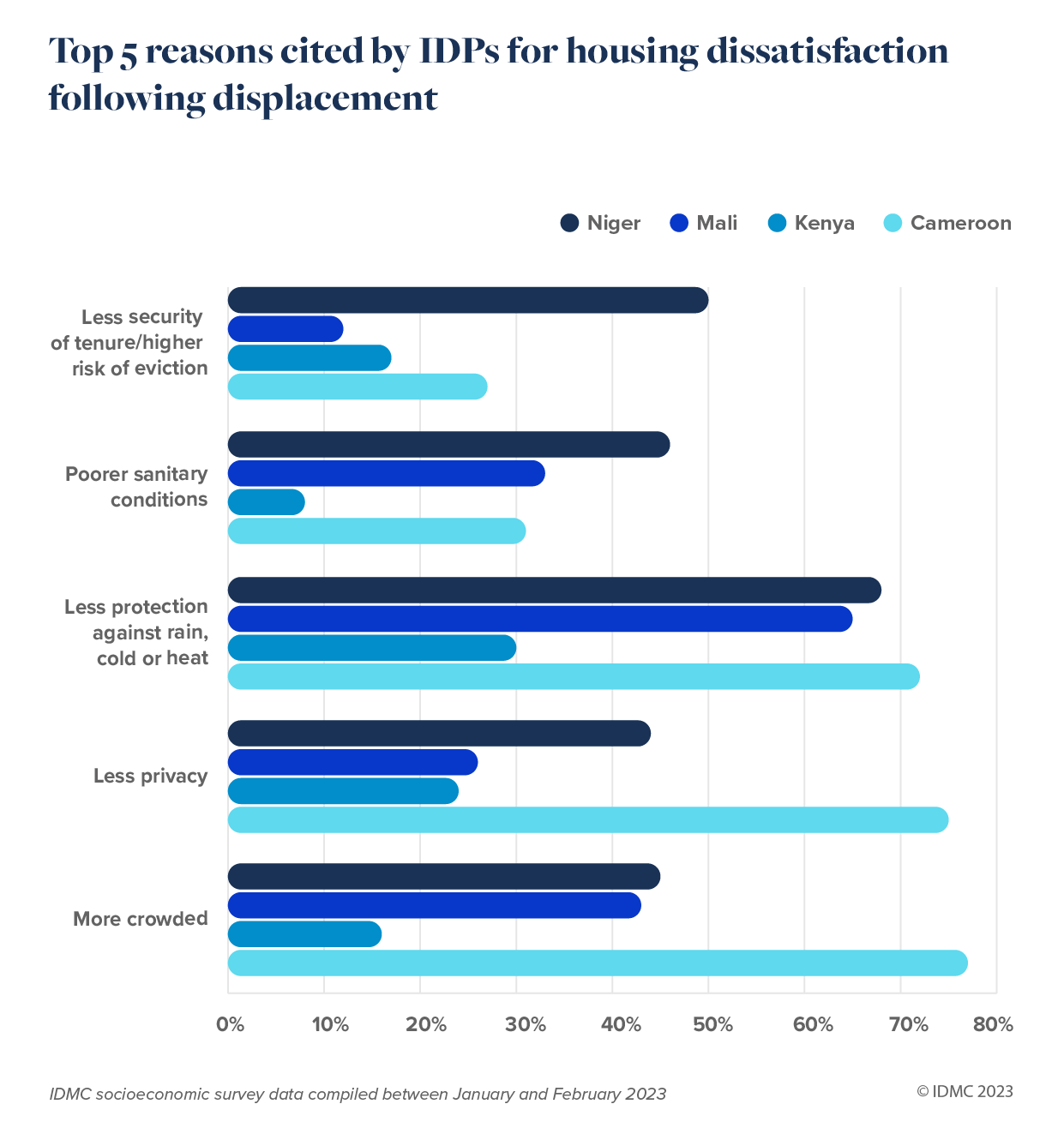

Across the four case studies, IDPs expressed lower satisfaction with their current housing conditions compared to before displacement, citing reasons such as overcrowding, decreased protection from external environmental factors, and reduced privacy (see figure 5). Moreover, the data collected indicates a significant decrease in homeownership among IDPs in all four case studies following their displacement. In Cameroon, IDPs surveyed had been relocated to campsites, meaning a drastic decline in homeownership rates, from 90% to 1%. In Mali, after rural-to-urban displacement, the percentage of surveyed IDPs owning homes decreased from 97% to 1%.

Concurrently, the arrival of IDPs resulted in increased household expenses for non-displaced respondents. In Kenya, for example, 77% of respondents hosting IDPs incurred additional housing expenses, compared with 48% of those not hosting. The main additional expenses reported were attributed to higher food prices (64%); the purchase of extra food, supplies, or furniture for IDPs (21%); and increased utility bills (21%).

Figure 5: Top 5 reasons cited by IDPs for housing dissatisfaction following displacement

Using the survey tool and its results

This tool can help humanitarian, development, and government actors gain a deeper understanding of the circumstances affecting both IDP and host communities. This insight can be of great value developing programming and policy-making efforts that are more likely to meet the specific needs of those affected by displacement.

We invite you to explore the datasets from this year's studies and to contact us about using the survey tool to collect data in your country. We can adapt the survey with questions to address the unique needs and requests of in-country partners, as well as specific contextual factors. Our goal is to work with operational stakeholders and policy makers to continuously refine the tool and improve the data available to help those grappling with the challenges of internal displacement to get the support and solutions they need.

Contact us to learn about using the survey in your work