Expert analysis

08 March 2020

Beijing Declaration turns 25: a time to celebrate or a cause for concern for displaced women and girls?

Across the world, events are taking place this week to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action – a landmark set of commitments made by governments for achieving gender equality and empowering women and girls. Yet a new IDMC report reveals that for internally displaced women and girls, there may be little cause for celebration.

Internal displacement can have a devastating impact on a person’s life, but if they’re a woman or girl, the impacts may be even more severe.

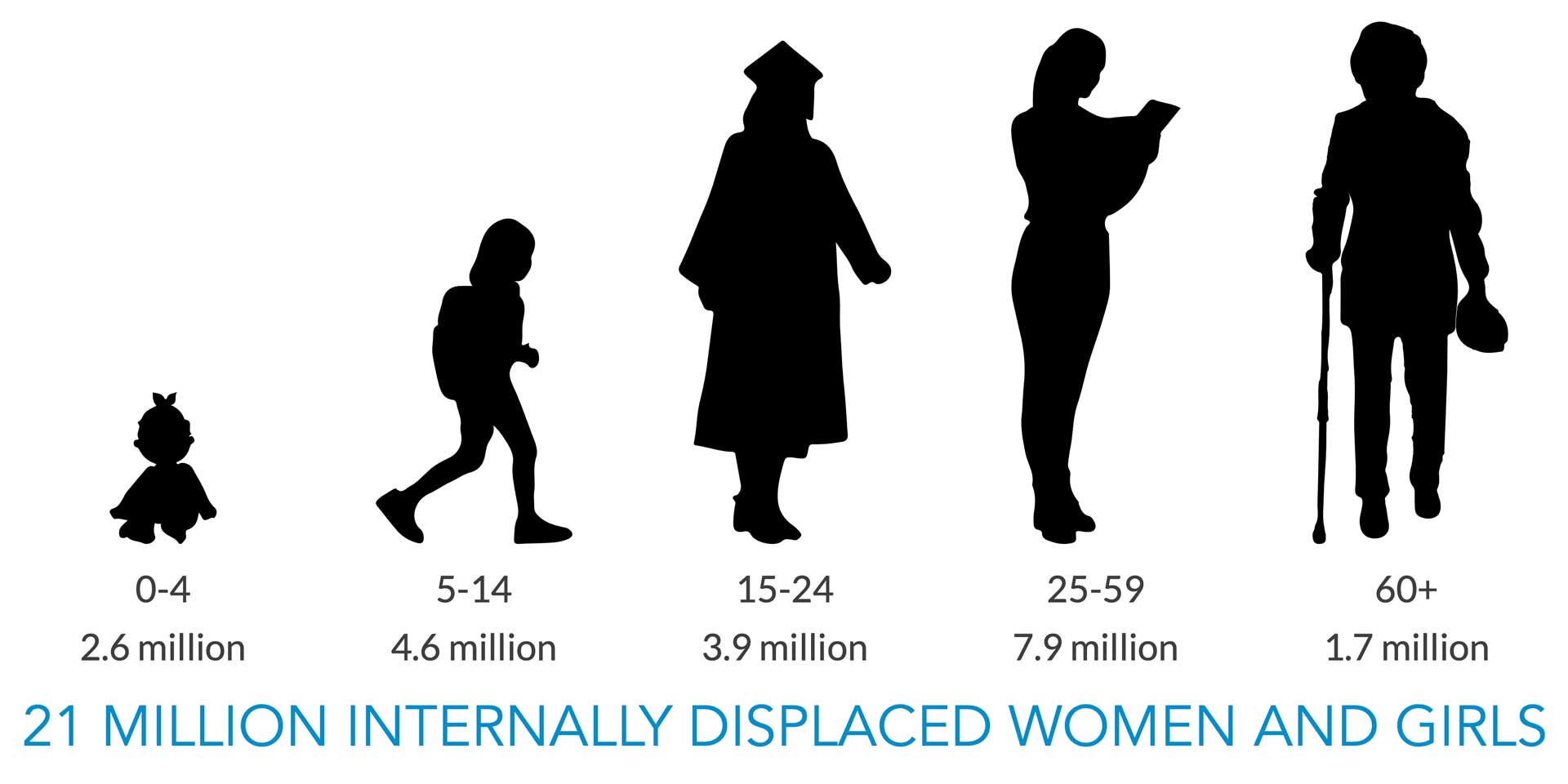

At least 21 million women and girls, or over half of internally displaced people (IDPs) worldwide, were living in internal displacement as a result of conflict and violence at the end of 2018. That’s more than the entire population of Chile, and the figure would be even higher if displacement in the context of disaster and climate change were included. Internally displaced women and girls tend to face more challenges than men and boys in accessing livelihoods, education and healthcare, as well as increased risks of violence and abuse.

These are the findings of a new report by IDMC, IMPACT Initiatives and Plan International, which presents the first-ever estimates of the number of women and girls living in internal displacement at the end of 2018 at the global, regional and national level for around 50 countries. Drawing on original data and analysis, the report highlights examples of good practice and areas of improvement for governments, as well as humanitarian and development organisations to fulfil their commitments towards internally displaced women and girls and take steps to address their specific needs.

What is the link between the Beijing Declaration and internal displacement?

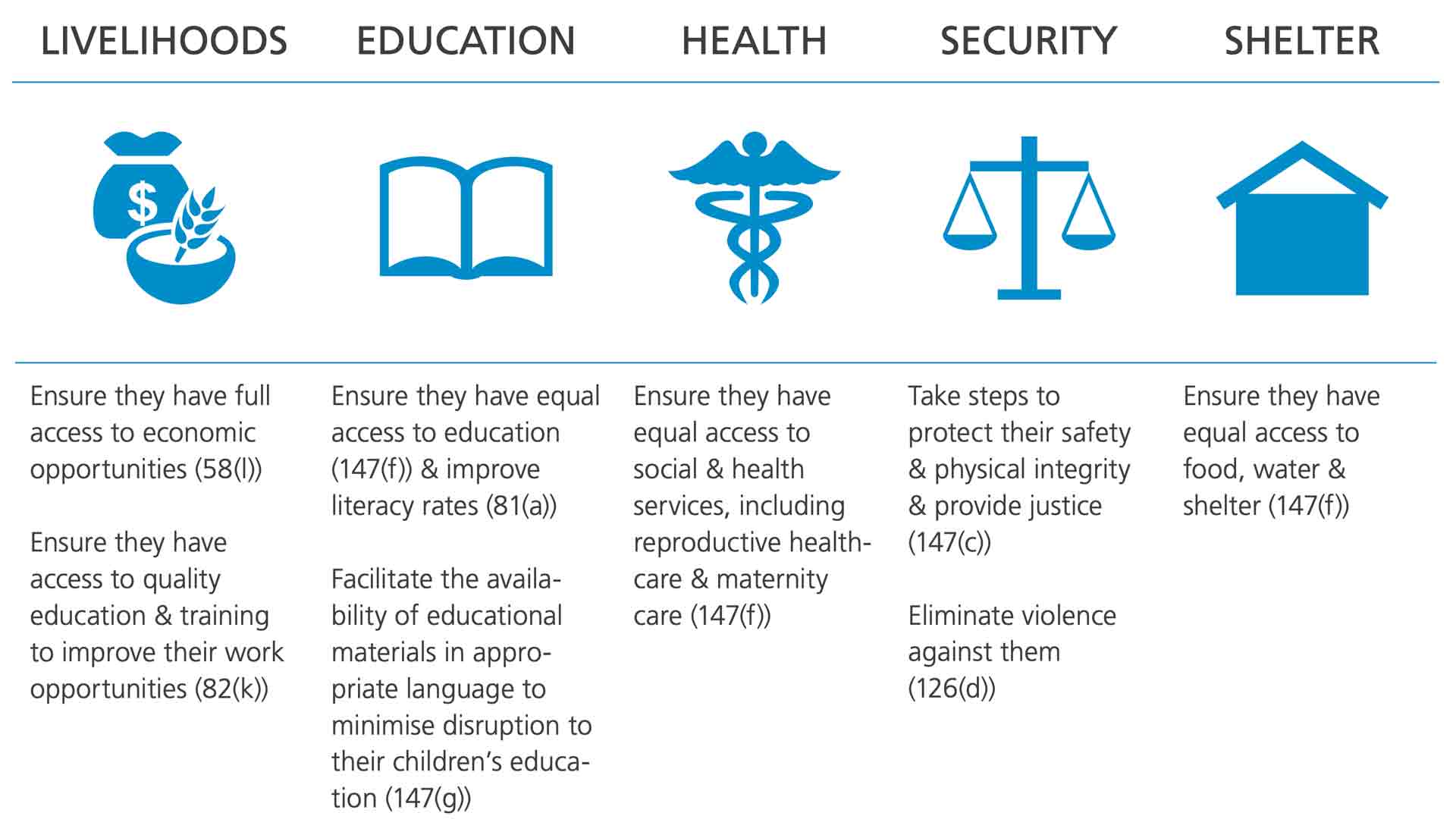

Produced at the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action calls for immediate and concerted action to assist women and girls to fully realise their rights. Protection, assistance and training for internally displaced women is a key strategic objective of the Beijing Declaration, and the text identifies actions that governments, together with non-governmental organisations, should take to support them.

The text has been adopted by 189 countries and is reviewed every five years to monitor implementation. Despite some promising achievements, progress at the national level has been slow and uneven. Dr Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women, expressed her disappointment at the findings of the last review in 2015, describing them as an “account of the world that has not, in the main, improved much for women and girls, and for some has got a lot worse”.

What challenges do internally displaced women and girls continue to experience?

This sluggish progress is particularly concerning for uprooted women and girls, given displacement can reinforce, and even amplify, women’s and girls’ pre-existing socioeconomic disadvantages. Displaced women often face greater challenges than men in accessing and maintaining livelihoods in host areas due to insufficient education, discrimination, lack of transportation, or childcaring responsibilities. For instance, in Nakuru county in Kenya, a survey revealed that women living in protracted internal displacement experienced the sharpest decline in their monthly income over a ten-year period compared with internally displaced men and members of the host community.

Girls living in internal displacement are also less likely than displaced boys to be in school. When displaced families cannot afford to send all their children to school, they tend to give priority to boys’ education over girls’, thus perpetuating gender disparities. Adding to this, displaced girls are at greater risk of gender-based violence and early child marriage, which can further disrupt their education and development. As one displaced girl in Cameroon explains, “Not all girls finish their education. Girls stop to get married, because of pregnancy or because of rape.”

Of course, not all internally displaced women and girls experience these challenges to the same degree; after all, displaced women, just like all women, are not a homogenous group. But persistent structural gender inequalities mean that women and girls are too often disproportionately affected by displacement, and that the impacts of this can be long-lasting.

Looking ahead and a call for action

While the report flags several successful initiatives to improve support for displaced women and girls, it emphasises that obtaining data on IDPs disaggregated by sex and age is key to providing them with the right resources. Recognising that women and girls must be engaged in the programmes that concern them and respecting their right to participate in decisions affecting their lives is also essential to finding lasting and inclusive solutions to their displacement.

The 25-year review of the Beijing Declaration, scheduled to take place at the 64th session of the Commission on the Status of Women in New York, should serve as an occasion to take stock of the progress that remains to be made in supporting internally displaced women and girls. Left unaddressed, the negative consequences of internal displacement will reinforce each other in a vicious cycle, potentially undermining valuable efforts to advance gender equality and slowing down crucial progress towards sustainable development.