Expert analysis

17 December 2018

"It's a time bomb" - protracted displacement and urban planning in Abuja

While attention of the international humanitarian community is focused on the crises in the Northeast, thousands of internally displaced people are stuck in limbo in Nigeria’s capital Abuja. And with a city master plan that has no room for accommodating destitute newcomers, their only hope is a new approach to urban planning that is starting to take shape among a few city authority officials.

As we approach Durumi Area 1 IDP camp in Abuja, leaving the bustling energy of Area 1 bridge behind, a rusty signboard announces the site. It is only readable from certain angles, half overgrown by bushes and trees; a signpost to an area not of transit, but of – if not permanence – something for the longer term.

Durumi camp was established – or rather, established itself – in 2014, after thousands of people fled the attacks on villages in the northeast of the country by Boko Haram. The extreme surge in violence early that year led to people fleeing beyond the towns of the northeast and far into the centre of Nigeria. Its capital Abuja became a destination for many as it was considered safe and a place of opportunity. Today, more than 1.7 million people are living in displacement in Nigeria due to conflict and violence. In the first six months of this year alone, 417,000 people were displaced in the context of conflict. In addition, each year hundreds of thousands are forced out of their damaged or destroyed homes by floods and an unknown number flees from shrinking livelihoods opportunities linked to water scarcity and environmental degradation across the country. Once displaced, many people join the ranks of the urban poor and live at risk of forced evictions in marginalised city centres.

Abuja is understood to attract increasing numbers of displaced, but current estimates of how many internally displaced people live in the city are shaky and official numbers do not exist. In Durumi, the 2,740 people in and around the camp all fled here in 2014 from the northeast, suffering four years of displacement with no end in sight. Although one would expect some semblance of semi-permanent infrastructure, past the entrance of the camp there are makeshift tents and shacks made from plastic sheets and pieces of wood under trees, a few toilet cabins made from corrugated iron sheets, and little else.

This looks like anything but a long-term solution. In Durumi, like in so many other towns and cities across the globe, the absence of tenure security means people hesitate to invest in expensive but sustainable building material. Instead, they make do with second-hand corrugated iron, plastic sheeting and plywood that they can buy at low prices at the Pantakers, nearby local markets.

We are invited into one of these shacks by Fatima Umaru. When Fatima arrived in Abuja in 2014 her family first moved into an unfinished house that had been left abandoned by its owner. She was lucky to find such a plot of land with a partly built house, she says, as it provided better protection and more space than they could otherwise afford. However, one day the owner of the house continued construction and Fatima and her family of six had to move out. Today, her house is a small shack with a tiny courtyard partitioned off with plastic sheeting, and all the cooking is done outside under the trees.

The trees are the main reason why she and many others chose to live outside of the walled plot on which the “official” camp is located. The little shade that the trees give makes all the difference in hotter months and tents can be more easily constructed underneath them.

Fatima’s shack looks a lot like the shacks in which many of Nigeria’s slum dwellers live today. Informal settlements have grown rapidly over the past decades across the country and 50% of the urban population is estimated to live in slums. However, urban planning processes, housing markets and basic service delivery in Nigeria’s towns and cities are not currently set up to accommodate informality. A bias against informal housing and employment is deeply rooted within administrative systems and procedures and will be hard to overcome.

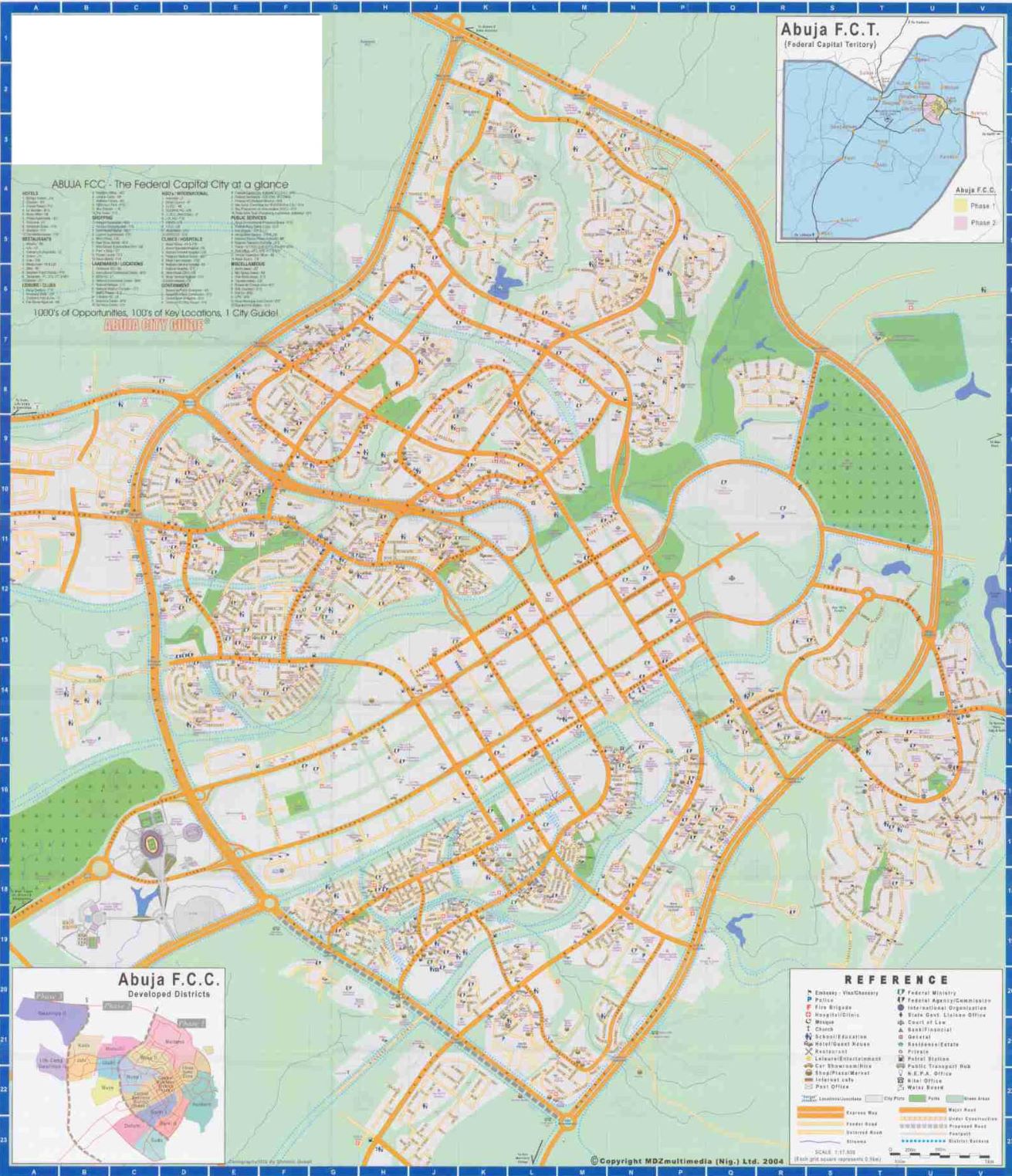

In Abuja it may perhaps be harder than elsewhere: Abuja was conceived as and still is a nation-building project. The new capital was proclaimed in 1976, to be developed in the centre of the country, where the cultural and ethnic diversity of the nation would come together under the banner of the new Nigeria. A master plan for the city was developed and construction began in 1979. Between 2000 and 2010, Abuja grew by almost 140%, making it the fastest growing city in the world. However, the original master plan remains the blueprint for the city’s planners and authorities. Unchanged for almost 40 years it is now at the heart of many, if not all, of the barriers to solutions for housing, services and jobs for the poor and the displaced that come into the city.

However, new forces within Nigeria and within city councils are emerging. Officially, the Federal Capital Development Authority of Abuja (FCDA) and the Abuja Metropolitan Management Council (AMMC) remain steadfast in their belief in and adherence to the original master plan of 1979. But within the institutions and in collaboration with independent researchers and urban experts, alternative narratives are evolving. A 2014 study, conducted by a group of researchers including an employee of the FCDA, highlighted the acute shortage of housing and proliferation of informal settlements accelerated by in-migration including from those displaced in the Northeast, and noted that “amid these challenges, and coupled with limited resources, the city administration is surprisingly trying to realise its elitist vision of an orderly and beautiful modern city.”

Others within the FCDA and the AMMC are adding their analysis and building a case for a more flexible approach to urban planning. As earning an income is a daily struggle for the Durumi’s internally displaced they are pleading for a new understanding of informality. For them it is clear that unless the notion of informality as illegality changes in the coming years, the displaced in Durumi and in the six other camps in Abuja are at high risk of becoming displaced again. This high level of vulnerability is of detriment to the city and to its function as a nation-builder. If the city does not capitalise on the skills and labour of informally settled communities, and with a growing number of poor without access to income and housing, the risk of insecurity is likely to increase. As Dr Chiahemba Nor of the FCDA mutters as we drive back to the centre, “it’s a time bomb”.

Next year, Nigeria will have been independent for as long as it was under British colonial rule, 59 years. It’s time to throw off the shackles of outdated ideas of blueprint urban planning and embrace the city as what it is: a dynamic and organically growing, interconnected system that is only as strong as its weakest parts. As strong as Fatima, her displaced family and her neighbours are allowed to be.

With special thanks to Dr Sherif Razak, Dr Chiahemeba Nor, Bashir Abdullahi and Zainab Gajiga for their support and insights.