Expert analysis

12 September 2019

Looking beyond Boko Haram in the Lake Chad region

IDMC's monitoring fellow for West Africa, Clémentine André, explores some of the underreported violence that has led to internal displacement in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria in the past couple of months.

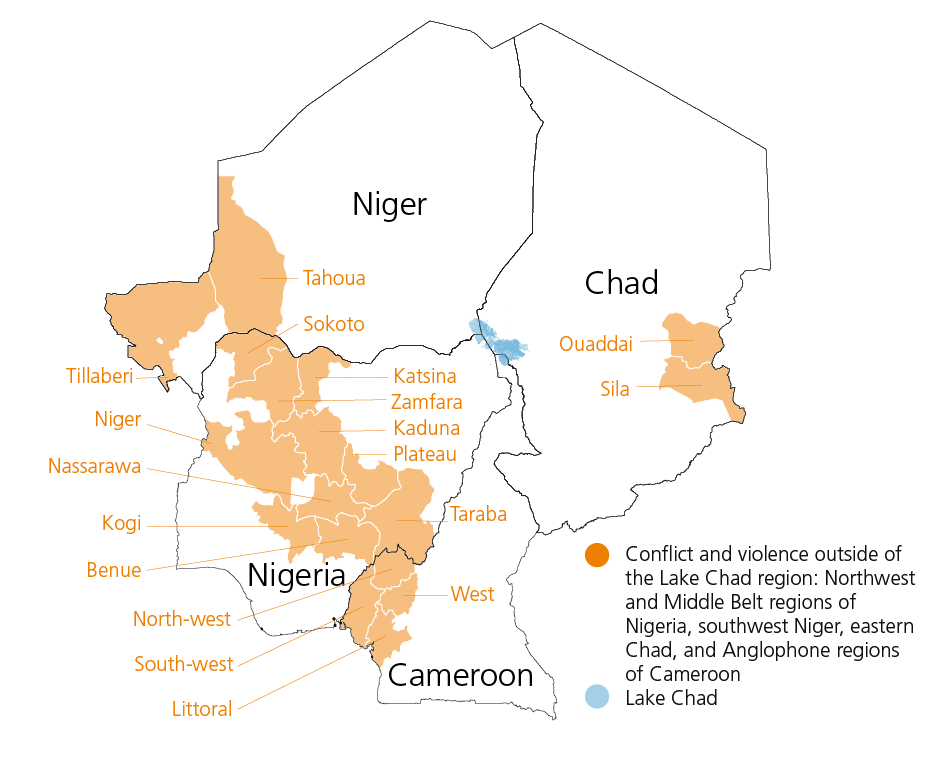

In recent weeks, many reports and articles have highlighted the dreadful milestone of Boko Haram’s 10-year insurgency across Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, which has forcibly displaced millions of people. Unfortunately, the Islamic extremist group, which has perpetrated large-scale human rights abuses and caused the deaths of thousands of people, is not the only driver of displacement in the region. Other conflicts have had a significant impact on people’s security but, with restricted access and limited data, they have been overlooked.

As we release our mid-year figures – which show that this complex web of violence in West Africa is driving high levels of displacement – we explore some of these overlooked crises and ask: has the decade-long insecurity in the Lake Chad region exacerbated these ongoing or emerging conflicts? Are the conflicts inter-linked, or should they be thought of as stand-alone crises? Why have they not received the same level of international concern and media awareness as the Boko Haram insurgency?

A cultural and educational crisis in the anglophone regions of Cameroon

There has been a significant increase in violence and new displacements in the anglophone regions of Cameroon in the past couple of years, as a result of growing tensions with the francophone-led government and the anglophone population in the Northwest, Southwest, West and Littoral regions. The conflict is culturally and educationally rooted and can be boiled down to what language should be taught and used in these regions. There were more than 437,000 new displacements in the impacted states in 2018 – 20 times more than in the Far North region, where Boko Haram regularly carries out attacks and where most displacements are usually recorded. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) has not yet been able to obtain any new information this year on the impact of the worsening conflict on levels of displacement for the anglophone population. The lack of information and access, owing to security challenges and the political nature of the conflict, has resulted in underreporting and, as such, a limited humanitarian response relative to the scale and severity of the crisis. International organisations and local media have reported the destruction of homes, looting of schools and violence against civilians as key triggers of new displacements. As of September 2019, however, we are still unable to say with certainty how many people have lost their homes, how many children are not attending schools and how many families have been separated in the past six months. This crisis, which is unfolding rapidly, requires further attention and assistance.

Criminal activity and violent acts in north-west Nigeria

IDMC recorded more than 74,000 new displacements between January and June 2019 in north-west Nigeria. These displacements were rooted in acts of banditry, criminal activities and communal clashes across the states of Sokoto, Zamfara and Katsina, at the Niger border. Although this crisis is not new, reports about its impacts have only recently surfaced. It has already caused more displacements this year than in the north-east states, which have long been the epicentre of the Boko Haram insurgency. However, the border states have received very little international attention and humanitarian presence. The evolving situation in the north-west can be thought of as rural banditry, which will continue to strengthen amid the breakdown of authority at the local and state levels. This has created a complex informal security situation in the three north-west states and has triggered the displacement of tens of thousands of families.

The violent spillover from Mali and Burkina Faso into the south-western states of Niger

The security situation has also deteriorated in Niger’s south-western states of Tahoua and Tillaberi in recent months. Niger has experienced an upsurge of violent attacks and clashes near its borders with Burkina Faso and Mali, and there have been at least 42,000 new displacements in the country since January 2019. Displacements in the south-western states have taken the form of preventative movements by a population fearful of violence and jihadist attacks, widespread explosive hazards and direct attacks against civilians from different militant groups. Another humanitarian situation is simultaneously unfolding in the southern state of Maradi, with an influx of refugees from north-west Nigeria fleeing violent acts of rural banditry. These northward population movements are likely to lead to a strain on natural resources, which are already scarce as Niger suffers the effects of climate change and longer drought seasons.

Intercommunal violence and ongoing clashes in eastern Chad

While data on the number of displacements in other parts of Chad is hard to come by, contextual evidence points to an increase in intercommunal violence in the country’s eastern regions. IDMC was not able to obtain any information of new displacements in 2018 for the Lac region, which has been most severely impacted by the Boko Haram insurgency. This does not mean that there were no displacements, but rather points to the lack of systematic data collection at the time. In contrast, between January to June of this year, there were over 44,000 new displacements in the Lac province. This illustrates the bigger challenges of data collection and dissemination in highly volatile and politicised contexts.

The convergence of crises in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria: the challenge of comprehensive and informed analysis on multifaceted conflicts

Clashes between farmers and herders in Nigeria’s Middle Belt states led to more deaths than the Boko Haram conflict last year. This intercommunal crisis in the country’s central states cannot be understood in its entirety however without assessing the impact of the Boko Haram insurgency over the past ten years, which has caused the southward displacement of thousands of Nigerians in search of cultivable land and livelihood opportunities. The displacements that occurred in north-west Nigeria as a result of criminal violence did not stop at the northern border, and more than 35,000 people are believed to have crossed northwards into Niger. In eastern Chad, ongoing communal violence cannot be seen as entirely separate from the worsening security situation in its eastern neighbour Sudan.

Though at times extremely different in their causes, all these crises cannot be detached from the overall unstable and highly insecure context of the broader region. The way they are discussed, addressed and treated is highly dependent on the information available. In many instances, the security situation – coupled with political sensitivities and the willingness (or permission) to share data – has meant that information is not updated as often as it needs to be. This can lead to a reduction in the overall humanitarian and political response and capacity to aid the displaced population and can lead to a displacement situation going unnoticed.

A crisis that lacks information and clear figures on the scale of displacements is likely to not generate the necessary interest, political will and resources as a well-covered conflict will. Beyond Boko Haram, this is what is happening right now in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria. The different crises across the four countries are a stark reminder that better data and information collection and dissemination are required for not only an improved humanitarian response but also for a longer-term approach to stability and prosperity in the region.