Expert analysis

15 August 2022

One year on: the Taliban takeover and Afghanistan's changing displacement crisis

Conflict, violence, and displacement have been an inevitable feature of life for millions of Afghans for decades. A year ago, on 15 August 2021, the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan, ushering in an end to the worst of the fighting, but not the country’s displacement crisis. Its patterns may have changed, but people being forced from their homes and unable to return continues to be a critical issue.

Fewer conflict displacements

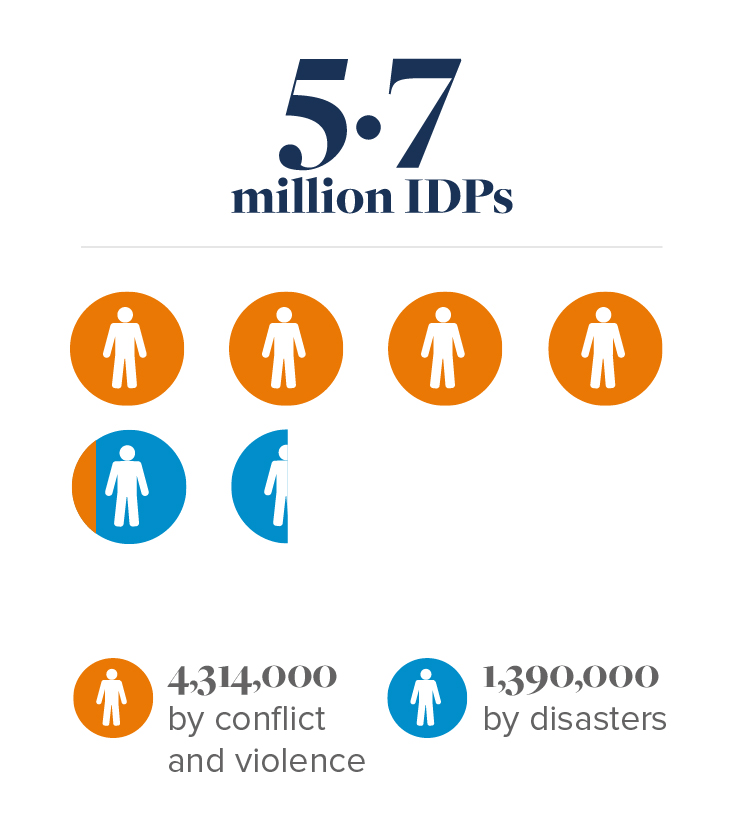

Conflict was long the main trigger of displacement in Afghanistan, accounting for three-quarters of the country’s 5.7 million internally displaced people (IDPs) and triggering an average of 380,000 new movements every year. The geographical spread of the phenomenon was also astounding. Every province recorded displacement or hosted IDPs during the last decade.

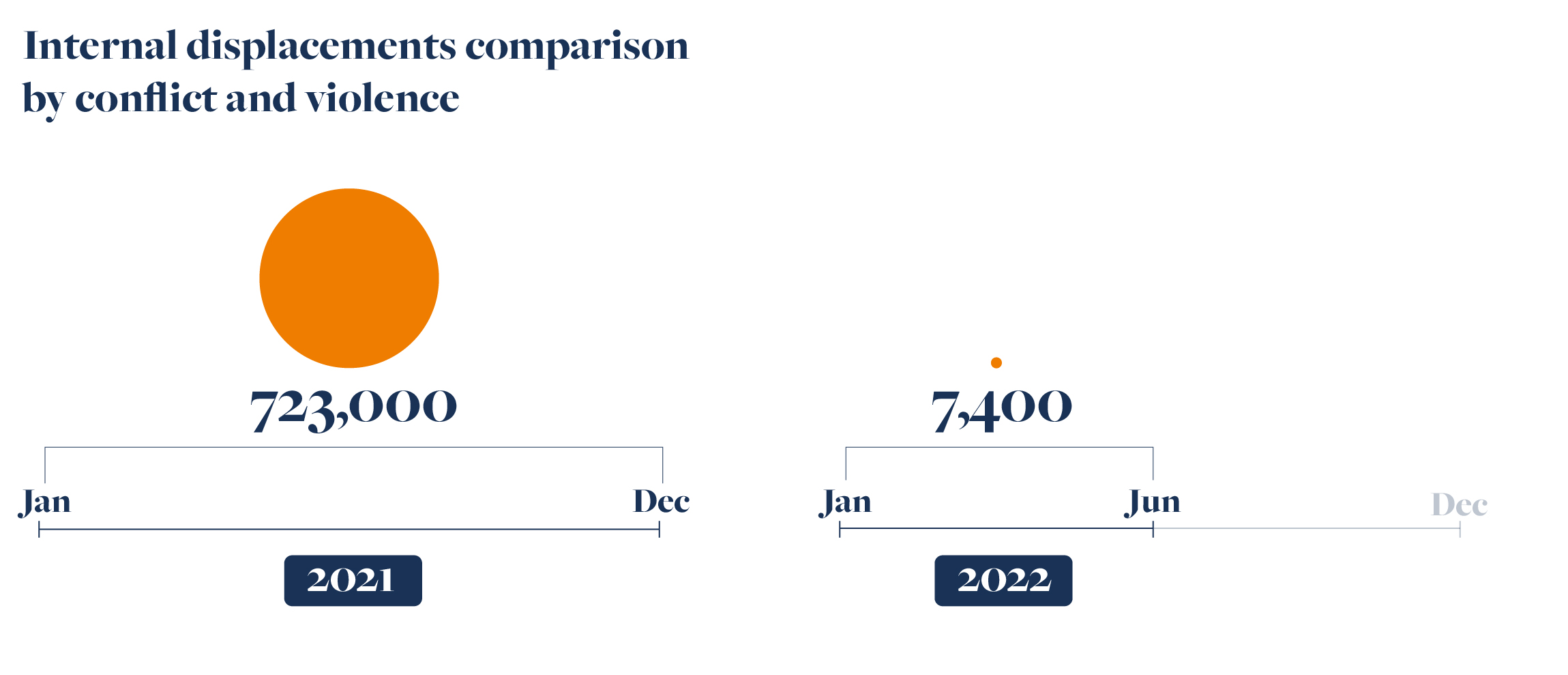

This changed abruptly when the Taliban captured Kabul, as conflict incidents and associated displacements decreased by nearly 100 per cent nationwide. Around 25,000 movements were recorded between August and December 2021, just four per cent of the total for the year. Conversely, the number of IDPs returning home increased to around three million last year.

The number of conflict displacements continued to decline in 2022 to around 7,400 as of 30 June, the lowest mid-year estimate we have ever recorded for the country. Conflict has been isolated and localised. People were forced from their homes in Baghlan and Panjshir provinces, hotspots of anti-Taliban resistance, and in Sar-e-Pul, where competition over natural resources has sparked conflict between de facto authorities and residents.

On the surface, this points to a positive development. After four decades, violence has subsided and so has displacement. Assessments from humanitarian partners, however, show there is more to the story.

Afghanistan is still grappling with one of the world’s most acute humanitarian crises. The economy is collapsing, a product of frozen state assets, limited sanctions relief and disruptions to international funding. Seventy per cent of families are unable to meet their basic needs, and the unemployment rate is expected to reach 40 per cent this year, a three-fold increase on 2021. More Afghans are taking on debt and sending their children to work to meet basic food, water, and healthcare requirements.

We know that displacement has a profound effect on the socioeconomic health of a country, costing an estimated $20.5 billion globally in 2020. The situation in Afghanistan shows that the economy also affects displacement, a phenomenon that is harder to capture and more complicated to understand.

Economic hardship is forcing people to move

Poverty, debt, and disrupted livelihoods are driving internal and cross-border movements. Among returning refugees surveyed in March, 33 per cent said they intended to leave the country again in the next six months, a figure that has nearly doubled since October last year.

Among internally displaced households, the economy is also a crucial factor in decision making, including about whether to move within or beyond Afghanistan. Sixty-three per cent of IDPs surveyed between February and April said their recent displacement had been influenced primarily by unemployment and/or poverty.

The exact dynamics of these movements are difficult to capture, particularly because economic migration can often be voluntary. One assessment, however, found that 56 per cent of people intending to move internally said their primary reason was a lack of jobs in their location, compared with 29 per cent who were seeking better work opportunities elsewhere.

This sheds light on the potentially forced nature of economic displacement in the country as many Afghans are facing such dire conditions that moving becomes a necessary step in coping with the economic crisis.

It is also keeping them from returning home

The economy is also a barrier to IDPs’ return. Only five per cent of displaced households said they intended to return to their province of origin as of April, down from 17 per cent last year despite pressure from the de facto authorities to go back to their home areas. At least 4,000 people living in informal settlements in Kabul have already been evicted.

Similar measures could put as many as 500,000 families at risk of homelessness, potentially creating another wave of displacement. Many IDPs who live in informal settlements have been displaced for decades, and economic opportunities and services in their places of origin are limited, making their sustainable return a distant prospect.

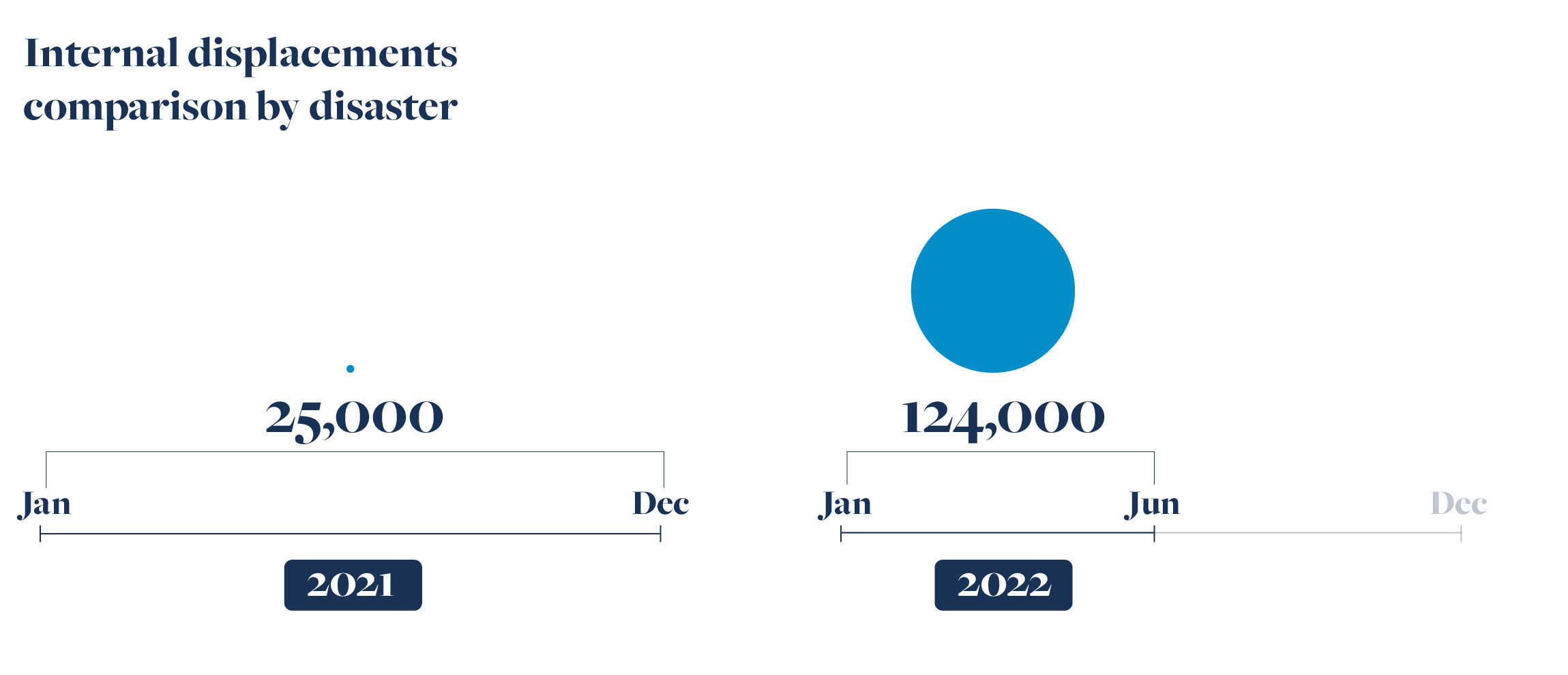

Such a move is even more unlikely for those whose homes have been damaged or destroyed by conflict or disasters. Flooding, drought, and earthquakes triggered 124,000 displacements between January and June 2022, five times the figure for the whole of 2021, and such events often result in housing destruction. Faced with limited resources, many IDPs are forced to choose between paying for necessities such as food and healthcare or building materials to repair their homes.

This is playing out in the aftermath of the June Khost and Paktika earthquake, which rendered tens of thousands of people homeless. Those in the hardest hit districts have expressed concern about being unable to afford to rebuild their homes and their risk of prolonged displacement as a result.

Solutions to displacement must consider economic factors

The bombs may have subsided in Afghanistan but displacement continues to affect millions of people, this time the result of an economic crisis that is driving the country toward universal poverty. Closing settlements and forcing people to return en masse will not resolve displacement.

A solution can only be found by establishing the conditions IDPs need to return to their homes or integrate locally, including by facilitating access to development funding, strengthening public services, and building community resilience.