Expert analysis

20 September 2019

The road from Yemen: Part 6

Deportations across Yemen’s invisible internal border: ‘This kind of thing will keep happening’

Political violence that broke out in Aden in early August after a missile strike claimed by Ansar Allah (also known as the Houthi movement) killed Abu al-Yamama, a leading commander of the UAE-backed Security Belt armed forces, has received much attention in recent weeks. The violence reignited rifts among members of the coalition fighting Ansar Allah, with UAE-backed forces accusing elements of the Saudi-backed Yemeni government forces of having been complicit in the missile strike.

The violence has since escalated and raises fears of a “civil war within a civil war” as the two groups vie for control of Aden and other areas in the south. It is not the first fighting between the Yemeni government forces and those backed by the UAE - the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and Security Belt forces - which support the secession of the south. It has, however, been the most destructive and worrisome and included reported air raids by the UAE on Saudi-back government forces that killed as many as 300 people.

Another event that took place in reaction to the missile strike but received much less attention, particularly in the western media, was the deportation from southern governorates of people from, or perceived to be from northern Yemen. Mass deportations of this kind also took place in 2016, as historical divides aggravate the country’s displacement crisis.

In Aden in particular, groups of people wearing Security Belt fatigues stopped shopkeepers, restaurant owners and day workers from governorates that formed part of North Yemen before the country’s unification in 1990. They beat them up, insulted them and threatened them with death if they did not leave the city immediately. People from Taiz were particularly targeted. The authorities and monitoring groups registered hundreds of displacements in early August, but the exact number is unknown.

We interviewed with some of those affected.

Ammar,* a 30-year-old construction worker living and working in al-Mansoura district since 2010, was stopped in the street with his five co-workers as they were returning from their lunch break on 4 August. He said:

“As we left the restaurant, a group of Security Belt soldiers stopped us in the street and asked us where we were from. We are all from Taiz and our response led to a beating and racist insults. There were about ten of them and they threatened to kill us if we stayed in Aden. We quickly went home, packed our things and left.”

They made the trip together, each then returning to their families’ homes in rural areas of Taiz. Ammar had been similarly displaced from Sheikh Othman district in 2016, when he and others were rounded up in trucks, dropped off in the middle of the desert and forced to continue their journey to Taiz on foot. He walked 30 kilometres that day.

“This type of thing will continue to happen, but I will return to Aden because this is my country and I am allowed to work wherever I please, wherever I find opportunities.”

Boutheina, a 32-year-old divorcee living with her three children in al-Mansoura district, was also among those forced to leave on 4 August. She had fled to Aden with her family from rural Taiz in 2015. The family had already been displaced a number of times in their home governorate because of the conflict and lack of employment. Once in Aden, her husband finally found work. When he filed for divorce, she decided to stay in the city and look for work herself. She bought a sewing machine and began to make clothes to sell. She was able to support herself and her children and felt stable in her new life, until she was uprooted again. She said:

“There was a loud knock at the door and when I opened, members of the Security Belt forces pushed me out of the way and began insulting me. They forced us out of the house and my kids were frightened and crying. I begged them to let me put on my abaya, but they didn’t let me. They said they would kill me if I went back inside. They looted the house and took everything, including my sewing machine.”

Boutheina took refuge in her neighbour’s house and first thing the following morning they hired a car to take her back to her family’s home town of Turba. Upon arrival, the driver refused to take money from her. She had gone through enough, he said. She and her children are now living at her aunt’s house with no source of income, but she said she would never go back to Aden.

“I was insulted and threatened. I’m not sure why, maybe because I’m an IDP or maybe because I’m a northerner. We can’t go back and I would never go back no matter what. The insults, the mistreatment and the fear for my children that I experienced there will stay with me forever.”

Other non-residents and even residents of Aden were also affected by the political tension and violence. Bassam was on his way from Hodeidah to a hospital in Aden to pay for his mother’s surgery when Security Belt forces detained him in Bureyqa district at the entrance of the city for a few days. They beat him up, put him on a truck and dropped him off with others in the middle of the desert to finish his trip back north through Taiz by foot. One Adeni family fled clashes in Dar Saad district and are still staying in a hotel in Turba.

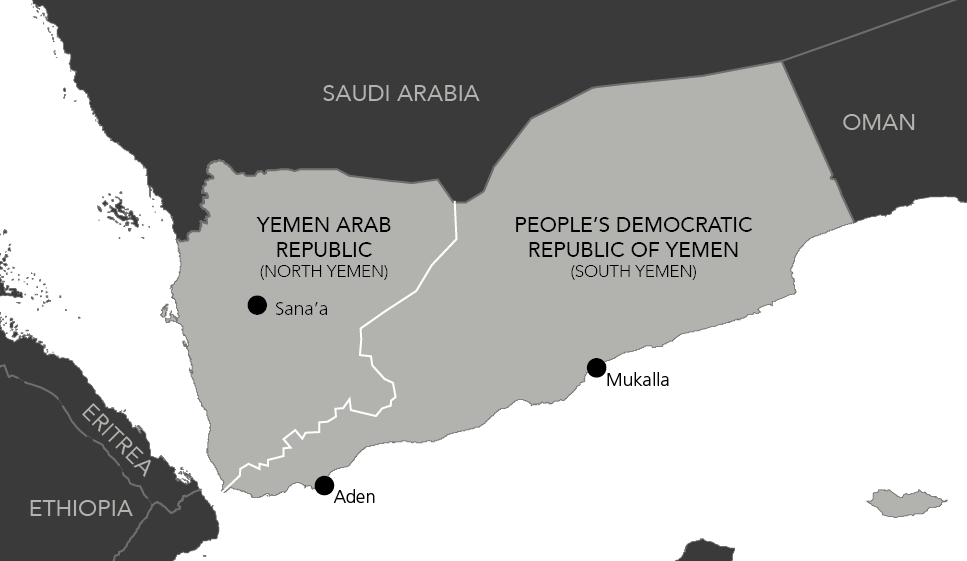

The question of the south’s status is almost as old as unification itself, and triggered a civil war between the two former countries as early as 1994. It also figured prominently during the 2011 Arab spring protests and was a major sticking point during the National Dialogue Conference in 2014, during which Yemen’s transition was being negotiated. It continues to be highly divisive in areas controlled by the coalition today, and the failure to resolve it has created an invisible internal border across which freedom of movement is not guaranteed. Those fleeing northern provinces in search of refuge or access to medical services or to pursue livelihood opportunities in the south may not able to do so. The latest escalation in the conflict makes such movements harder still.

The “southern issue” and the ongoing displacement across Yemen's internal border can no longer be ignored or shelved for later discussion. Any efforts to negotiate an end to the war must recognise and address it, lest it become the enduring spoiler in efforts to bring peace and unity to the country and durable solutions for the displaced.

*All names are assumed

Author: Schâdi Sémnani with interviews by Akram al-Sharjabi

This blog series is part of a broader research project on the relationship between internal displacement and cross-border movements along the displacement continuum, based on work by the Migration Governance and Asylum Crises (MAGYC) consortium and IDMC’s Invisible Majority thematic series. This is the second of several thematic discussions in the blog series on internal displacement issues in Yemen. In case you missed the first, read it here. Also read parts one, two, three and four from Europe and Djibouti.