Expert analysis

30 April 2020

Why more data is needed to unveil the true scale of the displacement crises in Burkina Faso and Cameroon

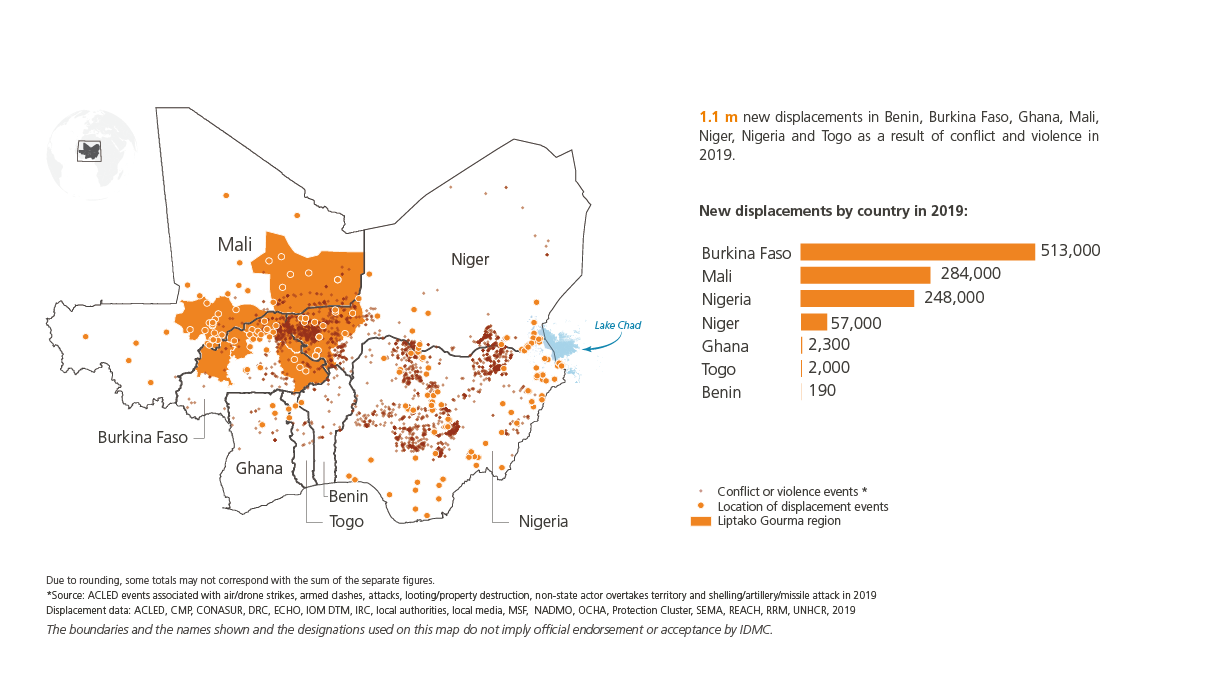

In our latest Global Report on Internal Displacement, IDMC highlights escalating violence in the Sahel region of Africa as a situation of grave concern. We report on how the worsening security situation in the Liptako Gourma region could spread to coastal countries such as Togo, Ghana and Benin, and how the ongoing conflict in the Lake Chad region continues to drive high levels of displacement, with little to no prospect of lasting solutions in sight.

This blog focuses on the anglophone region of Cameroon, one of the most neglected crises in the world in terms of the global attention is receives, and on Burkina Faso, revealed as the world’s fastest growing humanitarian crisis in 2019. While the two crises have different contexts, they share having the most significant underestimates for the number of internally displaced people (IDPs), across the region. This is owing to access constraints, political sensitivities, security concerns and strained resources. Though the available numbers are alarming, they do not allow for sufficient analysis to paint the full picture of internal displacement in both countries. Instead, the data reveals a significant gap in our understanding of these crises and their actual scale.

What we know

By the end of 2019, Burkina Faso reported 560,000 IDPs across the country, with the majority living in the Centre Nord and Sahel regions, bordering Mali and Niger, representing an alarming 1,100% increase in new displacements over one year. Such an increase is unprecedented and indicates a shift in the level of violence in the region, which is intensifying as a result of a multifaceted rural crisis. Armed militias are multiplying, including bandits, jihadists and self-defence groups. In 2019, Burkina Faso suffered more jihadist attacks than any other Sahelian country. In 2020, the numbers of newly displaced people continue to increase, and hopes for an improved situation are bleak. Near-daily attacks by jihadist groups and local militias have forced hundreds of thousands more out of their homes and has caused the closure of hundreds of health centres around the country.

In Cameroon, out of the 969,000 IDPs reported by the end of the year, the majority were living within the anglophone regions of Northwest and Southwest, bordering Nigeria. Growing tensions between the francophone-led government and the anglophone population have led to a significant increase in violence and new displacements since 2016. This overlooked conflict is culturally and educationally rooted and can be boiled down to what language should be taught and used in these regions. Most of the attacks take the form of destruction of property and direct violence against civilians.

The available data reveals worrying trends of an overall escalation in violence in both contexts, and reflects the dire humanitarian needs of the affected populations. The numbers do not, however, reflect how volatile security and restricted access tend to impact data collection, humanitarian access and aid delivery. Our understanding of these crises remains full of gaps.

What the numbers are not telling us

Unreported pendular movements of populations in Burkina Faso:

Many of the displacements occurring in Burkina Faso take the form of pendular movements, where families or communities are forced to flee more than once as a result of persistent insecurity and armed attacks. There is currently no system in place that monitors these multiple and consecutive movements. They occur daily, and at an alarming scale. With this significant caveat in mind, Burkina Faso was still labelled as the fastest growing conflict displacement crisis of 2019. As a result of the unprecedented humanitarian needs in the country and restricted access, owing to growing security concerns, the number of IDPs is likely not accurately reflecting the full scale of the situation on the ground and should be treated with caution. The current system to monitor IDPs is nascent, and is still adapting its methods for data collection, processing and dissemination of the number of IDPs. Available figures are likely significant underestimates; so more support and coordination are needed to centralise data management.

Limited assessments due to restricted humanitarian access in anglophone regions of Cameroon:

Humanitarian access is an ongoing challenge as humanitarian cargo has been destroyed or blocked by both parties of the conflict. This is significant as it does not allow for an updated understanding of the situation across the country. A crisis that lacks clear figures on the scale of displacement is likely to not generate the necessary interest, political will and resources needed to bring an adequate response. To this day, the anglophone crisis of Cameroon remains one of the most neglected humanitarian situations in the world. Attacks are ongoing in 2020 and reports of new displacements continue to surface.

Lack of data on drought displacement, sudden-onset hazards, and returns of IDPs:

Both contexts lack data and information on internal displacement linked to prolongated droughts, sudden-onset hazards (predominantly floods and landslides), and do not report or monitor the returns of IDPs to their place of habitual residence. In 2019, there was no information on disaster-related displacement in Burkina Faso. In Cameroon’s NWSW regions, information was very limited and displacement figures were difficult to come by. These are important factors to consider when trying to paint the full picture of internal displacement in these crises. They also reveal that, while Cameroon and Burkina Faso are two of the countries most affected by internal displacement, they also have some of the biggest limitations in data collection and dissemination, access to humanitarian assessments, and the delivery of aid.

Why these trends matter and require more attention and concrete action

In recent weeks, the Covid-19 pandemic has raised concerns in the two countries. There are fears that the virus will spread to hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people sheltering in makeshift sites throughout Burkina Faso. Many of the displaced populations live in temporary shelters, overcrowded houses and with limited or no access to clean water and sanitation. For the majority of the IDPs in Burkina Faso and Cameroon’s anglophone regions, social distancing is simply not an option. Both countries have confirmed cases of Covid-19. However, without a comprehensive understanding of the current humanitarian needs of the IDP populations, the response to this new crisis might be rendered ineffective. Better data is required for not only an improved humanitarian response but also for a longer-term approach to stability and prosperity.

For more information on displacement as a result of conflict and violence, and the methodology behind our data, please refer to the 2020 Figure Analysis for Burkina Faso and Cameroon.