Spotlight

14 May 2024

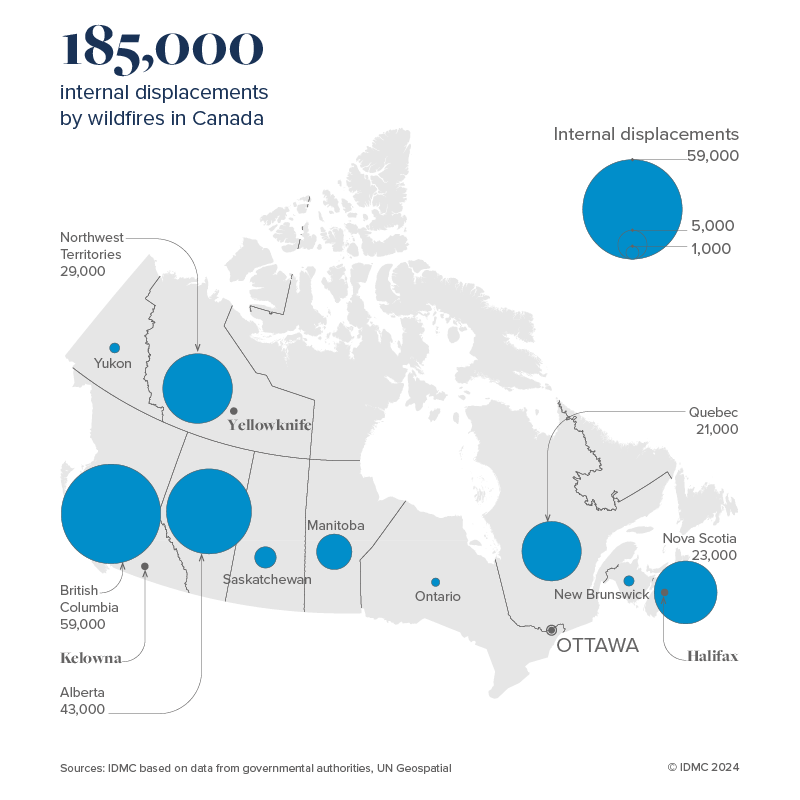

Canada - Record wildfires spread to urban areas

Canada’s hottest summer in 76 years fuelled the country’s most destructive wildfire season on record in 2023, when almost seven times more land than the annual average was burnt. The extent of the fires was such that they produced nearly a quarter of the year’s global wildfire carbon emissions. They also triggered 185,000 internal displacements, the highest figure since data became available for the country in 2008 and 43 per cent of the global figure for wildfires. The fires’ scale and impacts highlighted the need to strengthen the country’s risk reduction measures, evacuation protocols and overall disaster resilience.

Wildfires regularly affect Canada’s vast boreal forests and prairies, putting small communities living at the urban–wildland interface at heightened risk of displacement, housing damage and loss of livelihood year after year. Indigenous communities, 80 per cent of which live in areas highly exposed to wildfires, particularly suffer from repeated displacement, although no systematic data is available. Examples exist, however, such as the Lytton First Nation reserve in British Columbia, which had to be evacuated for the third consecutive year in 2023.

Beyond higher hazard exposure, this trend is partly explained by an approach to fire management based on population density and property value. As such, limited investment, including in infrastructure, has constrained remote communities’ ability to implement disaster risk reduction measures and recover swiftly from the impacts of disaster displacement.

Communities living in large urban agglomerations have generally been spared displacement, but this trend shifted during the 2023 wildfire season, when almost half of the movements recorded took place in urban areas. The largest event of the year, which accounted for nearly a quarter of the total displacements countrywide in 2023, occurred in mid-August when a fire broke out near the cities of Kelowna and West Kelowna in British Columbia. As it approached the west bank of Okanagan Lake, which splits both cities, authorities issued evacuation orders for 45,000 people, more than all the displacements recorded nationwide during the severe 2021 wildfire season.

Another 23,000 displacements were linked to the evacuation of Yellowknife, which is home to half of the Northwest Territories’ population. It was the first year wildfire displacement was recorded in the sparsely populated territory and such a large-scale evacuation was unforeseen. Despite the armed forces’ intervention and the provision of additional flights, numerous challenges arose. The only highway out of the city was heavily congested as some people had to drive 1,500 kilometres to find emergency accommodation in the neighbouring province of Alberta.

On the other side of the country, the eastern province of Nova Scotia, which usually enjoys a more temperate climate, reported its biggest wildfire on record in late June. The blaze triggered almost 17,000 evacuations from the suburbs of the capital, Halifax, and the rarity of the event caught many unprepared. Some residents struggled to find evacuation routes or reliable information on how to respond to the threat.

Mindful that wildfires are likely to become more intense and destructive as global temperatures rise, the Canadian government has taken steps to strengthen disaster preparedness and risk reduction. Its first national risk profile, published in 2023, sets out concrete measures to further reduce wildfire risk. The government has also invested in the FireSmart programme, which raises public awareness about risky behaviours, advises on the use of fireproof building materials and reinforces evacuation protocols. The FireSmart programmes for some indigenous communities integrate traditional knowledge and cultural norms and values into their provisions. Indigenous knowledge, including about controlled burns and the planting of fire-resistant tree species, is also being considered in other fire-management strategies and plans.

The need to decentralise responses has also been highlighted in disaster risk management and climate adaptation strategies, which see the role of provincial authorities as key. In British Columbia, which has experienced four of its most severe wildfire seasons since 1919 in the last seven years, the seasonal wildfire service was changed to a year-round one in 2022. Taken together, these initiatives should help to reduce future wildfire displacement risk.

For references and additional information, please see the full report.